This book is the one I waited for most anxiously, having read Seán Hewitt’s debut pamphlet Lantern last year. It didn’t disappoint. Right from the opening poem, the quiet, but not at all understated Leaf, you have some idea what you are in for:

For woods are the form of grief

grown from the earth. For they creak.——

For even in the nighttime of life

Tongues of Fire p. 1

it is worth living, just to hold it

This collection is all about grief, chiefly for the slow death of the poet’s father from cancer, but also the deaths of friends and contemporaries by suicide, and the loss of love. The book is heavy and heartfull with grief, but it is not a sad book. It studies darkness and night, but also light, air and water.

It is essentially a ‘moniage‘ book, a going out into nature to discover wisdom and meaning, and it is full of trees, birds and plants. The poems about wild garlic and St John’s Wort are among my favourites, and I wish I had come across the latter when I did the St John’s wort newsletter! But Oak Glossary

In oak,

essential nouns include soil,water and time – these are produced

Tongues of Fire p16

from their elements. Water is a high

and gentle noise of clearest quality

which results from branches dripping

and I Sit and Eavesdrop the Trees show the poet entering deeply into the life of other living things, rather than discussing how they figure in our lives. As a gay man in a very Catholic environment, the poet must consciously go ‘outside’ to think about his relationships and sexual identity, and he discovers a place full of secrets, danger and death, but also strength, wisdom and love.

The crux of the book is Hewitt’s ‘versions’ (as opposed to direct translations) of Buile Suibhne, the twelfth century Irish epic about a king who is cursed with madness by a monk, and has to live in the woods among the birds (I can’t find any justification for the assertion that he becomes a bird himself in the translations available to me). Seamus Heaney produced a translation in 1985, and I’ve found it useful to compare the two. Heaney’s Sweeney is a very physical, forceful disruptive man, reacting with violence whenever he is crossed, and rampaging about Ireland

poking his way into hard rocky clefts,

Sweeney Astray p.10

shouldering through ivy bushes

unsettling falls of pebbles in narrow defiles

wading estuaries

breasting summits

trekking through glens.

He winds up in Glen Bolcain, a valley of madmen, where he has to fight for the best of the wild watercress, and he is ‘flailed’ by the thorn bushes where he has to sleep, and battered by falling from branches which don’t bear his weight. He is always on the defensive, getting into fights with people who comment on his plight, and the weight of the poem falls on the loss of the social world he used to inhabit.

Hewitt’s Sweeney is quieter, and more introspective, lonelier and more vulnerable

no matter where I go

my sins follow. First,

the starry frost will fall

at night onto every pool

and me left out in it, straying.

Hewitt focusses on the friendships Sweeney forms first with the madman Fer Caille whom he meets in Britain, and with whom he agrees to protect each other until Fer Caille’s death, and then with the monk Moling, through whom he is healed, and who mourns his death. People have often seen this poem as a clash between an oppressive Christianity, and a more pagan pantheism, but in this version, Hewitt seems to create an reconciliation between the two worldviews, without necessarily giving ascendancy to either.

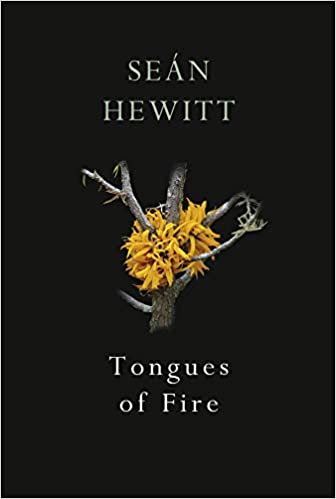

I find this elsewhere in the book, particularly in the final section – Tree of Jesse and the title poem Tongues of Fire, which is a reflection on the fungus clavariiforme (you can see it on the cover), which he finds in the woods, and also on the Pentecostal tongues of flame. In spite of the close attention to Biblical motifs, it is not exactly clear who or what he asks

for correlation – that when all is done,

Tongues of Fire p.69

and we are laid down in the earth, we might

listen, and hear love spoken back to us.

My own reflections on our relationship to the earth and the question of moniage in particular, will be a long time brewing, but start here. This is a stunning book.