New Workshop - Leaf Support

February 17, 2026 Reading time: ~1 minute

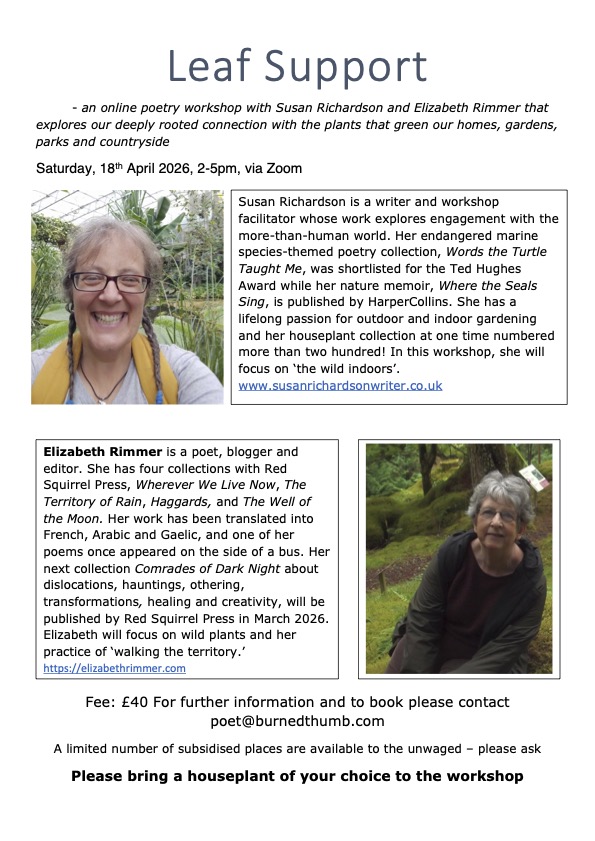

My friend Susan Richardson and I have collaborated to develop a poetry workshop, which will have its first on-line appearance on the 18th April. Please get in touch at the email of the flyer to ask for further information and to book a place.

Twice Its Weight of Tears

January 21, 2026 Reading time: 4 minutes

Do you recognise the phrase I used in the title? It appeared once on the side of a bus to advertise an installation at Inverewe about plants and landscape - in this instance bogland. It came from a poem I wrote about peatlands and climate chane, inspired by the nature reserve in Unst, but I've illustrated it with pictures of Flanders Moss, which was the nearest peatland to where I used to live. You can read the full poem here. However, it appears that you don't have to have read the poem to have heard the phrase though. I came across it in the introduction to a book about bogs, used without any reference to the context. I'm not complaining,however. It means that it has become part of the zeitgeist, like 'the winter of our discontent' or 'I can haz cheezburger', which is rather nice, I think.

Do you recognise the phrase I used in the title? It appeared once on the side of a bus to advertise an installation at Inverewe about plants and landscape - in this instance bogland. It came from a poem I wrote about peatlands and climate chane, inspired by the nature reserve in Unst, but I've illustrated it with pictures of Flanders Moss, which was the nearest peatland to where I used to live. You can read the full poem here. However, it appears that you don't have to have read the poem to have heard the phrase though. I came across it in the introduction to a book about bogs, used without any reference to the context. I'm not complaining,however. It means that it has become part of the zeitgeist, like 'the winter of our discontent' or 'I can haz cheezburger', which is rather nice, I think.

However, I have a book coming out, which I have to promote. Rishi Dastidar has a timely article in the Society of Authors magazine about branding which made me think a bit. What is my 'brand'? If you didn't know my work, how would you introduce it? It's easier now than it was twenty years ago - more people have heard of geopoetics, where I started, and there is more focus on place writing and eco poetry than there used to be. It has close observation of the seasons, weather, landscape and plantlife, raises questions of territory and belonging and the impact of political upheaval and the climate crisis. But they don't read at all like me. Partly, they are more focussed, slower-moving, and much more technically sophisticated. They make me feel shambolic and flashy. They feel grounded as much in the poetry tradition as in the earth, and they impress me with their intelligence and thoughtfulness.

But also, they don't quite satisfy me. They feel cerebral and artificial, like gameplaying with words. They do it so well, but they are short on delight. They feel professional, classical. By default, then, I have to ask myself if I am a Romantic amateur, relying on inspiration and vibes and just wanting my poetry to be 'lovely', which I am not. I spent a long and highly entertaining (as well as useful and revealing) period last year diesntangling my mental health issues from my ADHD, and I have come to the conclusion that I am in fact a medievalist. The problem I have with the new generation of place poets is that they are running, I think, on the post-Enlightenment polarity of intellect and emotion, which lines up imagination and delight with the emotions, and sense observation and analysis with the intellect. The Will, in this dichotomy is a free-floating observer, constantly forced to choose between emotion and intelligence, like Captain Marvel, playing off duty and pleasure and law and freedom against each other.

I am inclined to follow the philosophy of Richard of St Victor, a Scottish twelfth century monk, who separates the faculties of the soul into Reason and Love. He has his own purposes for this, which I am less invested in, but the interesting thing is that Reason, and Imagination line up, and Love is paired with Sense. Wisdom is a function of Reason and the Will and pleasure are functions of Love. Reason may plot the navigation, but Love is the Captain.There is a hierarchy in this, but there is also harmony.

My 'wallking the territory' practice then is about creating delight. The wilder way I can connect folklore of Fae folk with the way we treat refugees, a nest of crickets with a hyperactive child, a political upheaval with a ballad, is a function of a not only a passionately held attitude, but thoughtful speculation. I need my poetry to flow, sound well, spark appreciation of the plants or skyscapes I write about, but also, just as much, to be scientifically accurate, and philosophically coherent, and to speak to the heart as well as the brain. It is a big ask, and I am at the stage of a book's gestation where I am not confident I have achieved anything like what I wanted. But the process of asking myself who I am has been fascinating. I am the poet who draws parallels between bipolar depression and peat bogs. I wrote

Sphagnum can absorb

twice its own weight in tears.

Condemned to be Cultural Beings

January 6, 2026 Reading time: 3 minutes

This is a phrase from Leonardo Boff's book Cry of the Earth, Cry of the Poor, which connects ecology and liberation theology in a way I have drawn from since the mid eighties. Many of the 'Valiant Women' I mention in my long poem The Wren in the Ash Tree (Haggards 2018) demonstrate this worldview, and many of the makers, permaculturalists and writers I follow and learn from are increasingly drawn into it as world politics descends into end-game capitalism and supremacist thinking.

But Boff also points out that a shift towards greener industries, more inclusive politics depends not only on adopting better strategies, but also a shift in mindset. He points out that we do not exist in isolation, but through the medium of our interactions with other beings, and more particularly, other people.

I’m logged in all the time, to a web

of constant dialogue, the garden, river,

weather, birds - the whole jingbang.

(from Whooper Swans, The Well of the Moon, 2021)

More than that, our dialogue is not simply transactional, an ebb and flow of benefits and damages, but involves knowledge and understanding, and a sense of the sacred, which he uses in a way that does not limit it to the awareness of the divine. The world is more than a mirror of ourselves, it is full of the 'other', the different, the unknown, and we must reverence it in order to deal with it in a way that will enhance all of us. In such a world, culture cannot be an add-on, a mere nice-to-have when the important things are dealt with. It becomes the essential tool for justice, for peace, for healing and reconciliation, for joy - and at this moment when all digital life is threatened by the use of AI, for our very survival. To understand ourselves and our place in the world, to express it, to listen and engage with all the other beings of the earth as they are, rather than how we can make best use of them, is what it means to be fully ourselves.

Herbs and Poetry for Reclaiming What Was Lost

November 6, 2025 Reading time: 3 minutes

For years poets have mentioned Kamau Brathwaite's essay, History of the Voice, but I have never managed to track it down until someone on Bluesky kindly gave me a link and honestly it is one of the most interesting things I have ever read, creating links between my thinking on herbs as well as poetry, via colonialism and healing, and tying up with geopoetics and some work Mairi McFadyen was doing about culture and the body, and the discussion the young folk-singer Quinie had on her blog about 'singing like a bagpipe'.

Brathwaite discusses the way 'nation language' Brathwaite's useful term for the common language developed by the mixed populations of colonised people, which I will use henceforth, and culture was erased in Jamaica, and Western culture imposed. Scottish people who were told for generations to 'speak properly', that Scottish was 'slang' and not to speak Gaelic at all will understand this process, but it was taken much further in Jamaica. We are used to being marginalised and under-represented in literature syllabuses, and we know that pub quizzes will expect 'everyone' to know about the Tudors and Plantagenets, not the early Stuarts or the Lords of the Isles, but colonised communities were told they had no history or culture at all and were graciously introduced to the glories of Wordsworth or Shakespeare as gifts of the Empire. The result was children writing essays about snow falling on meadows rather than rain on canefields, poets writing in pentameters rather than the rhythms of nation language.

It goes further than this - Brathwaite says that pentameter

carries with it a certain kind of experience, which is not the experience of a hurricane. The hurricane does not roar in pentameter. And that's the problem: how do you get a meter that approximates the natural experience, that is the environmental experience?

I have come across two examples that demonstrate this in music. One is the Mongolian band Anda Union, who play the music of nomadic people following thier horses across the steppes. It is full of the sounds of wide open grasslands and the drumbeat of horses' hooves. The other is the psalm singing of the Scottish islands, which embodies the wind and high seas crashing on the shores of Lewis. I think this process is what Lorca means when he talks about duende in flamenco - it summons the spirit of place, which gives poetry its vital depth and truth, and I think it is what Quinie means when she talks about connecting her singing with place and its people. Building such a poetics is powerful and necessary work.

In a similar way, to recover and reclaim knowledge of plants, growing skills, cooking and crafting traditions can connect a people to a place and a community. Learning the herbs of a place connects me to the soil and the rainfall, the tastes and preferences of my neighbours. But I can also connect to the history and heritage I bring with me, my mother's cooking, what friends have shared with me. The herbs and the poems

mend a link

in the chain that leads us back to our dead,

and makes us whole, wherever we live now.

Latest Newsletter

October 31, 2025 Reading time: ~1 minute

The latest newsletter, The Day of the Dead, is out and you can read it here

Banking Up the Fire

October 21, 2025 Reading time: 2 minutes

It is a wet, grey, still morning. The summer is over and the garden is quietly sinking into itself, with only the last marigolds and a few rogue Welsh poppies left, sparks against the wet soil and the grey painted fence. I can see the bluetits in the damson tree now, as the leaves thin out, and the robin is taking full advantage of the cleared spaces to find food in my footsteps. I'm banking everything down now, the garden, and, now that Comrades of Dark Night is with the publisher, the poetry, for the quieter winter, while I plan for the next bit.

My attitude to the garden has been enthusiastic but unfocussed so far. I've tried to get to know it - the soil, the weather, the gradient, sun and shade, I've put all the interesting herbs I could find in it, and grown them as well as I could. Learning about herbs has been a passion which I have indulged and written about for years, but of late something else has grown out of it - you can't do much about herbs without discovering a long history of cultural appropriation, neglect, suppression, forced exile, extractivism, environmental degradation and simple contempt for traditional learning and culture that goes alongside it. I want my garden to reflect some of that. I am going to focus on growing the kind of plants that are iconic in their own countries, but threatened by over-harvesting or environmental despoliation - the za'atar and Cretan thyme of Lebanon, white sage of Native American territories, the rose and rhodiola of Bulgaria, and our own cowslip and pasque flower. And I'll be looking at the issues thrown up - biodiversity loss, war, the rigged capitalist market, misinformation and the gate-keeping of learning.

It all sounds a bit grim. But you go to the herbs for healing and nourishment, colour and delight. You can't look at the herbal traditions withoout coming across myth, legend, music and poetry. The South African cellist and composer Abel Selaocoe begins his joyous and wonderful concerto Four Spirits with the movement MaSebego, giving thanks to traditional healers “for bridging the gap between the modern world and the advice of our ancestors.” I want my garden, and my writing, to reflect some of that too. Maybe we can learn to build a few more bridges, make some more poetry, cook something tasty, share a little time of peace.