Stonehaven may well be my new favourite Scottish town. In spite of the nightmare of cancelled trains, the journey turned out to be lovely – I must admit, Scotrail staff are enormously kind and helpful if you get caught up in this kind of thing. I was only just thinking how much I missed the open fields at harvest time, but going up through the East coast big sky country, there were fields of wheat, packed heavy and still in the gentle morning sun – how good the weather was! – hayfields all harvested and open to the sparrows and finches, cows and sheep, white houses knee deep in the hedgerows and little green wooded river valleys.

Stonehaven itself is lovely. I’m not sure what I was expecting – something industrial and abandoned perhaps – but it isn’t like that at all. Its seaside resort days are past their best, but the lovely stone houses are still there and the main street and market square have interesting shops and evidence of a thriving artistic community. And there’s the harbour and the sea, though I didn’t have time to see them.

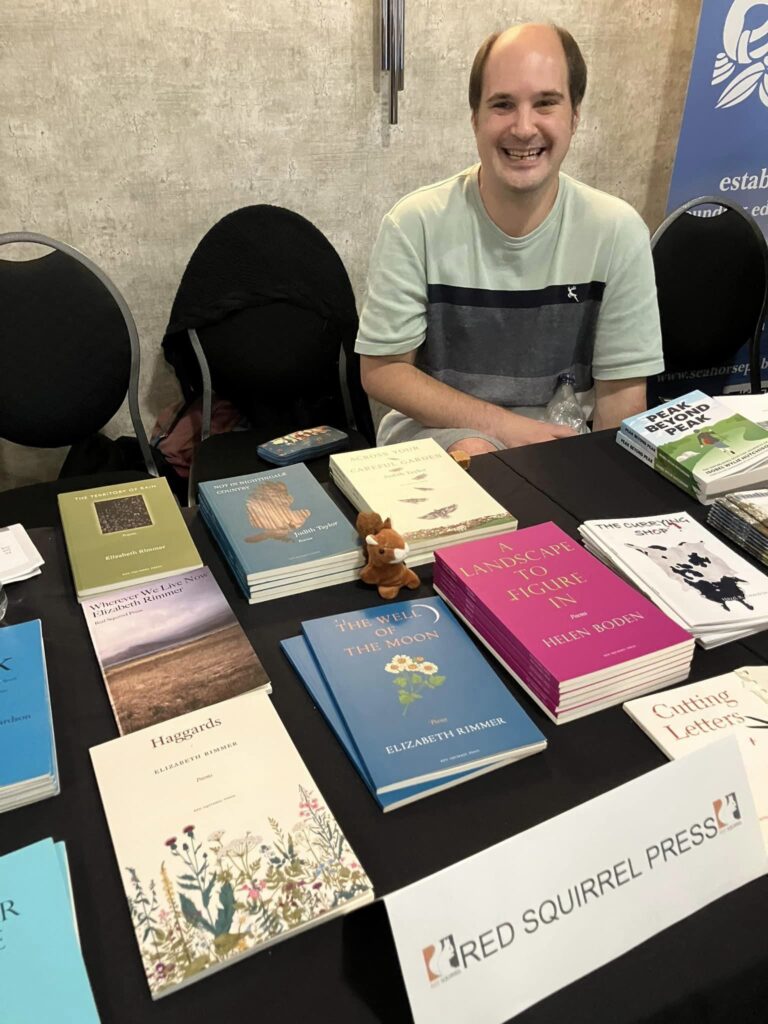

The Festival is brilliant. It is very well-organised – communications from the organisers have been uniformly timely and helpful, and the venue Number 44 Hotel was very generous and hospitable. I hope they made a packet from all the poets and friends who came, because they deserved it. The contributors are a rewardingly diverse bunch – different levels of experience, different genres, different backgrounds – and the audience was the warmest and most receptive I’ve seen in a long time. I sold a book, and bought three – that’s how these things go – and we swapped books and news and met and made friends as happens at all the best festivals. And heard some great poetry.

The squirrels: From left to right – Carolyn Richardson, Edwin Stockdale, Judith Taylor Helen Boden (behind), Elizabeth rimmer, Tim Turnbull, Hazel Cameron.

Thank you to everyone who organised, participated, attended or otherwise enabled such a lovely day. Especial thanks to Judith Taylor who organised the showcase in the absence of publisher Sheila Wakefield who is still battling long-term illness, and to Edwin Stockdale who – with Judith – manned the stall. I’m really looking forward to furthering my acquaintance with both the Wee Gaitherin and the lovely town of Stonehaven next year.