My daughter refers to StAnza as my PoetryCon. As in Convention, like ComicCon which features so often in the Big Bang theory. There’s not so much cosplay, though somebody did once enter the Slam wearing a powdered periwig, (my daughter begs to differ – ‘You ALL dress like poets’, she says) no film stars and very little merch except books, but she is right. Though she says it’s more nuanced than that. She is a comic artist herself, and says that StAnza is not so much like the big Cons, where readers go to see the re-enactments of their favourite comics, more like one called Thought Bubble, which is where comic artists go to hear their favourite artists talk about how to write or draw comics, and engage with the function comics perform in the wider worlds of art and society. As well as displays and panels, book signings and sales, there are outreach events within local communities, and a strong grass roots presence.

This describes the much-loved atmosphere of StAnza as we have come to know it. I have been to other festivals, and I do get the impression that they are places people drop into for the highlight events, and the big names, and then maybe tack on something attractive that is happening in the day or two they are there. That is not how StAnza works. For years I have been trying to write a StAnza-based parody of Christy Moore’s Lisdoonvarna because I can’t think of anything else that comes quite so close:

Everybody needs a break

Climb a mountain or jump in a lake ——

We go there and they come here.

Some jet off to … Frijiliana,

But I always go to Lisdoonvarna.

We go to St Andrews. We go for the whole thing. We book tickets recklessly and we go to everything we can until we fall over. You can see people dashing between venues to get from one event to the next, and the B&Bs and pizza places and coffee shops are full of poets all the time. The Byre Theatre is a hub,

Ramble in for a pint of stout,

you’d never know who’d be hangin’ about!

Well, you get tea and scones, during the day, or coffee and shortbread, though there is usually a lot of alchohol drunk later – and you get the gossip. This year, after a two year hiatus, it was like a dam bursting. We had a LOT of catching up to do!

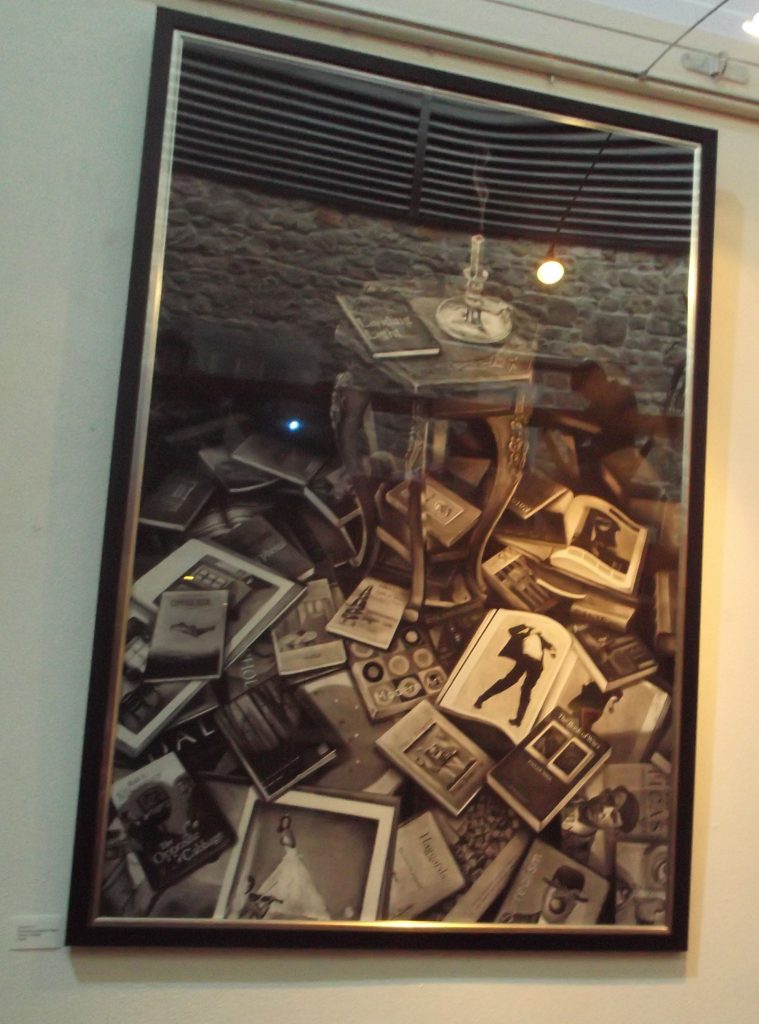

Of course the big names are there. I’ve seen Jackie Kay, Don Paterson, Caroline Forche, Mark Doty, Gillian Clarke, Moya Cannon, Seamus Heaney and John Burnside. I’ve seen poets from all over the world. I’ve seen poetry films, comics, installations, performance poetry, music. The big name poets don’t just perform, they hold workshops and round tables, panel discussions and protests. They do sign books, but you can also find them hanging about in the Byre. There are plenty of book sales – Innes Bookshop during StAnza is the only place you can see poetry bookshelves raided and empty like a late night bakery stall, and the Poets Market is a valuable lifeline and showcase for small presses and pamphleteers.

But there is also a strong grassroots presence. The independent Scottish presses are there. The developments in newer poetry are represented and showcased alongside the familiar and established trends. Fledgling presses have the opportunity to test themselves against the heavyweights, and poets who might have found themselves at a distance from livelier centres get a chance to hear what’s going on and contribute. We compare notes, and collaborate, develop new projects and make new connections. When I came to Scotland there was what we called a ‘Scottish cringe’ – a feeling that Scottish culture was provincial, nostalgic, undeveloped – and that you needed to attract the attention of London to make an impact. I honestly think that has gone now, and events like StAnza, with its emphasis on encouraging Scottish, Gaelic and Shetlandic alongside English, and its confident opening of doors to a multi-cultural perspective, has had a lot to do with it. A tall tree needs deep and wide-spreading roots, and here is where we grew them. One performance poet said of StAnza, ‘You took us seriously when we didn’t know how to take ourselves seriously’.

If I felt that this dimension was lacking this year, I’d have to make a few qualifications. Clearly covid took a flamethrower to most of our assumptions and habits. Long-term planning after last year’s wonderfully light-footed and ingenious digital version couldn’t really start while new variants and changes of regulations were happening all the time, and applying for funding in such a challenging environment must have been a nightmare. You couldn’t predict how many people would be able to come, or feel confident in sharing spaces, especially as a lot of us aren’t exactly spring chickens, and travel was difficult and unpredictable even before the Ukraine situation happened. Also – and this took me by surprise – we had looked forward to being back among our tribe so much and we were so excited to be there, that the experience became intense and overwhelming. We weren’t used to being around so many people. We weren’t used to travelling. We lost things, forgot to pack things, locked our keys in our hotel rooms (just me? I don’t think so!). We got tired and emotional. My daughter used to talk about ‘con drama’ – a cocktail of too many people, too many events, not enough food and less sleep – and we all felt it. Some of us started cutting events earlier than usual, some went home early, a few of us got ill and had to stay in bed instead of getting into the things we’d come for. It wasn’t the same.

But then, how could it be? Things were inevitably going to change, and if we felt understandably disappointed, we need to think of new possibilities. But I would like to think we could appreciate what we had without being simply obstructive. This year had some real gems of highlights. My favourites were poetry from Vahni Capildeo, Hannah Lowe and JL Williams, discussions about Modernism and TS Eliot from Paul Muldoon and Sandeep Parmer, the lecture about the discussion of migration and human rights in poetry by Mona Arshi. Other people loved Robin Robertson’s reading, William Letford’s verse novel work in progress and the discussion of erasure poety and narrative by Alice Hiller and Gail McConnell. We had the extra curricular delights of gulls, the beach, pastries at the poetry breakfasts, fish suppers and reunion pizzas with people you only see at StAnza. We hung out in the Byre as usual, much to the bafflement of the staff who kept warning us the bar was closed. It was lovely.

Feedback questionnaires are going to be online this year, so we missed Annie’s ‘fill in your phones and turn off your questionnaires’, and I will have to think very carefully about how I raise some of the issues on my mind. I know the hard-working and invariably courteous and helpful StAnza staff and volunteers pulled off their usual marvel, and I want to give them my unqualified thanks and appreciation.

We will definitely be back next year, with our blank notebooks and empty suitcases for all the new poetry. Floreat StAnza!