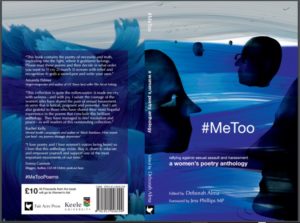

#MeToo – rallying against sexual assault and harassment

a women’s poetry anthology

Edited by Deborah Alma

This first response to the #metoo protest last year is not what I expected. In a counter-intuitive way it reminds me of Black Panther, in that its primary impact is not the big obvious issue, but the unusual experience of hearing the people concerned talk about it among themselves, in the way they want to talk. It is a wide-ranging, reflective, steadying read, though by no means an easy one. The poems in it were written not merely in reaction to recent events but composed over a long period, and it contains some which have been published before – but really, we should have expected that. Abuse is not a recent phenomenon, the protests of women are not evidence of a ‘new puritanism’, or a revisionist criminalisation of everyday behaviour. The lives of women worldwide and over many generations have been shaped not only by individual acts of aggression, but also by the long silence, denial, indifference, blame and collusion that prevented us from understanding just how much abuse women have to deal with. In a terse, carefully controlled and understated three blunt lines, Sarah Doyle sums it up

Enough tears. Enough silence. It was all of us but we

never knew. Sisters, take my hands, we can say it together:

me too,

me too

me too.

#Metoo Sarah Doyle

The anthology ranges over the whole gamut of experience, impact and outcome – not just violence, but gaslighting, threats, manipulation, guilt and fear. In Parental Guidance by Sue Hardy Dawson it asks what we should tell our daughters to keep them safe, without destroying their trust. It asks about the consequences to the next generation in Louisa Campbell’s What You Do When Your Child is Born of Rape. Emma Lee recreates the dangerous landscape of an ordinary walk home in The Landmarks Change When You Walk Home. Poems like It Didn’t Mean Me by Gill Lambert discuss our right to name our experience, and the consequences of doing so, Before Myra by Angela Topping or not as in Keynote Speech by Angi Holden.

The abusers referred to in this book are not only men, and the abuse is not only sexual. The poems are not only angry or distressed. Vasiliki Albedo’s Why I Didn’t Marry Him holds a masterly balance as she paints a picture that is equally generous to both sides of a relationship with two faces, one genuinely loving

He toured 47 apartments with me when I was thinking of moving,

and never complained when I didn’t.

Because he invented his own language, and taught me.

and the other terrifying

If he were not the one who settled his debts by poaching

my father’s watch, or who jumped

over the gate and wouldn’t leave when I called the police.

Poems may be simply done with all of this:

With my armoured finger separator

It was just so tiresome to have to do

Me Too. Me Too. Me Too.

Just One Example Jemima Laing

or sarcastic:

I put away my heart and the stillness inside.

I smile and say so what do you do tell me again and

how many kids do you have remind me again of your wife.

I Have Been a Long Time Without Thinking Kim Moore

They may be resilient:

I grew a thicker skin, got more guts,

clearer vision. Sharpened the points of my horns.

The Inequity of Goats Stella Wulf

or defiant like the two girls hiding in their tent with their pen-knives while strange men prowled outside in Jean Atkins Travelling.

Poets have written less in anger or self-pity than out of compassion for sisters abused in childhood, friends or colleagues whose situations we failed to understand or address, women we meet professionally who may be walking into disasters we can’t prevent or have crafted ways of surviving we admire and celebrate.

The greatest benefit of this long gestation is that these are mature and well-crafted poems, handling their load of grief without melodrama or self-pity. Poems like An Ancient Settlement, I Have Been a Long Time Without Thinking, Fidget and Wildwood will stay with me for a long time. The collection has been carefully curated to move through difficult territory without overplaying its hand, and its final section, Make for the Light, with its poems of healing, consolation and survival sounds a triumphant conclusion.

There are millions of seeds in pots and jam jars,

spilling from mouths of paper bags

one for each minute of each day lost,

copses, forests, wildwood

falling through my fingersI reach for the hands of my children, my sisters,

our dormant stories stir in earth

make for the light

Wildwood Deborah Harvey

But as Jess Phillips points out in her foreword, it is the sense of sisterhood that drives the collection:

Our sisterhood makes us want to stand together, it makes us feel the pain of another on a familiar path. Our sisterhood created #metoo and it was in the comfort of someone else’s bravery, nudging us to pass it on.

we stand together, each one a Spartaca

no longer silent or alone: each voice stronger,

massing, alive, a wild murmuration

of me too/me too/ me too

Spartaca Pippa Little

Please come to the reading from this anthology at StAnza on Thursday 8th March 6:15 – 6:45. Tickets are free, but you can now book them here.